Up In Smoke: Successful Couple Come to Tragic End

By Kristin Davis

The Virginian-Pilot

Ken Weitzner and his guests lounged at a booth inside The Palazzo, their heads tilted toward flat screens broadcasting college basketball a dozen hours a day.

March Madness 2010 had begun, and Las Vegas was its epicenter.

Weitzner sipped water and ordered a steady supply of beer for the employees he counted as friends. He'd brought them here, paid for their flights and rooms at the sleek Encore hotel.

The big-time gambler was in his element.

At home in Chesapeake, Weitzner lived the quiet and unassuming life of a family man. In Vegas, he was a big shot.

Weitzner launched one of the first Internet gambling portals 15 years earlier and made a fortune. He owned a million-dollar house with a pool and an apartment on 3 perfectly kept acres in Hickory and often talked about six-digit bets he'd won and lost while too drunk to care.

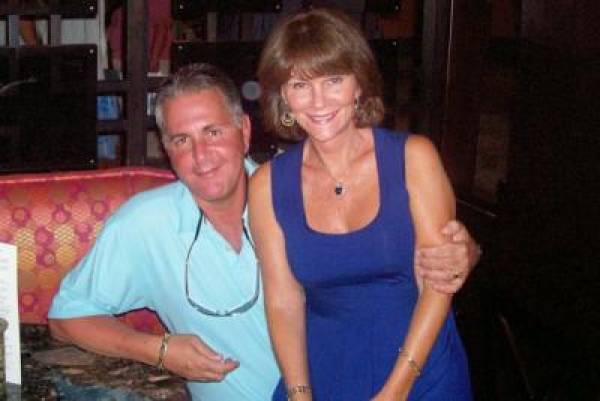

Weitzner was sober now, had been since 2006, and talked as much about his wife and grandkids as the business. He'd soon turn 54 and looked it, with gray hair and a handsome face that had just begun to droop.

He was, by all appearances, a successful and generous man.

Nobody knew Weitzner was about to go bust - or that perhaps he had already.

Weitzner found his place in life in high school.

He was a teenage bookie who sold parlay tickets to classmates at his Long Island prep school.

They'd choose four football games from a list, then guess the winner for each. Pick all four correctly and win a $10 prize. Any less got them nothing, which was generally the outcome: odds of a win were 16-1.

But just about anybody would pay a dollar for a chance to make 10.

Young Weitzner clandestinely used the schoolcopying machine to run off the tickets - or so he thought.

The machine was off-limits to students, a transgression beside the point once the school saw what was on those papers.

He got suspended.

Years later, Weitzner would tell that story whenever someone asked how he got his start.

But it did not all take off from there.

Weitzner's father and grandfather were doctors, and he would follow that conventional path - for a while. He had no interest in medicine, except for the illegal kinds he'd discovered by the time he entered Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk.

Weitzner spoke frankly in a 2007 interview with Tom Somach, a Pennsylvania-based freelance journalist who has covered the online gambling industry since its inception.

In that hourlong taped conversation, Weitzner talked about his medical background, his business practices and the monotony of marriage.

"I was forced into it," Weitzner said of medical school.

Weitzner used drugs, drank and gambled too much - a trifecta of addictions that connected like links on a chain.

By his own count, Weitzner amassed a dozen DUIs between 1980 and 2000 but never did any time. He would be accused of prescription fraud. "I was such a freaking drunk and drug addict. I had to cheat my way through medical school," he told Somach.

Weitzner specialized in psychiatry but never passed the medical boards. "I flunked them, like, three or four times."

Weitzner confessed to falling so deeply into gambling debt in college that his mother, a well-spoken woman from Hungary named Marika Somerstein, had to sell some of her things to help him out of it.

He would later make it up to her - exponentially, he said, and if it affected their relationship, mother and son moved passed it.

Weitzner was a mama's boy at 54, tending to Somerstein with daily phone calls and regular visits. They spent their birthdays - just two days apart - together. He lit up her life. He made her laugh.

After medical school, Weitzner returned to her in New York.

"For two years, I was able to have a temporary license," he said in 2007. "I prescribed drugs for myself and my friends. Many prescriptions."

After a stint in New York, Weitzner moved south again. He'd been taken by it, Somerstein said, ever since he was an undergraduate at Emory University in Atlanta.

Hampton Roads became home, and at 35, Weitzner married Jackie Ballance of Norfolk. She was a few years older, with two sons. She called herself Scarlett on the Internet and shied away from the fame and scrutiny that would soon find her husband.

Those who met Jackie called her classy. She dressed well, kept a trim figure and wore her dark hair in a chic bob. She kept a photo of her grandkids in matching plaid at Christmas on her Facebook page. She lunched with her sons and spent Sundays with their families.

By the mid-1990s, when words like cyberspace and e-mail were creeping into everyday vernacular, Weitzner was already online.

He wrote a newsletter Somerstein likened to a "Dear Abby" for men. Weitzner analyzed upcoming games, offered betting picks and touted his expertise as a psychiatrist.

He became The Shrink.

Gambling websites - illegal when operated in the United States - were opening in Antigua and Jamaica and Costa Rica. Suddenly anyone with a computer and a credit card could make a bet.

The American Gaming Association would estimate $5.9 billion in revenue from U.S. players alone in 2008 - $21 billion worldwide - for offshore gambling websites.

In the beginning, "these places needed a way to advertise," Somach said. Most mainstream American publications wouldn't risk the backlash.

Weitzner saw an opportunity.

He turned his newsletter into an online gambling portal and called it The Prescription. The Shrink would boast as many as 35 advertisers at his peak. He claimed to make $100,000 a month or more from the banner ads that blinked across his website.

He gained credibility as a conduit between bettors and bookmakers, said John Kelly, a one-time business partner.

Notoriety followed. "To get on top of the industry," Kelly said, "he stepped on a few toes. He wasn't loved by all."

Two images of The Shrink emerged: that of an industry watchdog and that of a double agent.

The Shrink made a living off the sportsbooks he supposedly monitored, said Chris Costigan, a former Weitzner employee who started the website Gambling911.com.

At best, it was a conflict of interest; Weitzner would report struggling sportsbooks only after he retrieved his own money from them, Costigan said.

Costigan considered that cheating.

New portals popped up, but The Shrink hovered near the top in those early years. He sold The Prescription for $2.4 million five years after he started it.

The Shrink launched a second gambling portal in 2005.

Eye on Gambling would do what The Prescription had done, offering up a place to talk about sports betting or whatever happened to be on your mind, to share stories and make friends with faceless strangers who went by fictitious first names.

But this was a new decade and a new climate.

"It's gotten very, very competitive," Weitzner told Somach in 2007. "Any gambling portal that says it's not struggling - they're lying."

Those banner ads that numbered in the thirties shrunk to about a dozen on his site. "The lowest ever," The Shrink said.

Portals were a dime a dozen, and this was the age of the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act.

The 2006 law would make it illegal for U.S. banks and credit card companies to collect debt from online gambling sites.

The long-courted American customers were liabilities, explained Somach. Those quick, easy credit card transactions of old spelled legal trouble, and a refusal to enforce payments spelled financial trouble.

The books soon sought business elsewhere, and sites like Eye on Gambling suffered most.

Still, it was a well-trafficked website and Weitzner had other ways to make money, like working as a "beard" for a big-time gambler - bigger, even, than The Shrink. Weitzner would use his own name to place bets for somebody else and take a cut of the winnings.

In 2008, he won $80,000 in a football handicapping tournament in Vegas.

Weitzner built a sprawling and stately 7,600-square-foot house in Hickory Estates with a fireplace in the master bedroom; columns around the deep master tub; a rec room outfitted with a billiard table and a jukebox; a detached garage; and a white picket fence.

In 2008, the IRS put a $74,000 lien on that house, which he later paid.

This kind of contradiction defined The Shrink and his trade.

Gambling is like gravity; what goes up eventually comes down.

Weitzner held steady as a cutthroat with questionable business tactics and as a loyal friend who would bail you out of jail and talk you through the toughest night of your life.

"I am no saint," he wrote on Eye on Gambling last July, "and I have lots of character defects that I work to improve upon."

He'd jump in his backyard pool with the grandkids as if he was as young and unblemished as they were. His public persona remained upbeat.

Alone, in the throes of depression and addiction, Weitzner would search the Internet for painless ways to kill himself.

"I read that drowning was actually supposed to be euphoric," Weitzner said on his portal in 2006, "but the thought of water filling my lungs and suffocation did not appeal to me."

His lifestyle had turned his skin shades of yellow and gray, "like a pineapple," Weitzner wrote. He'd hurt everyone he loved.

He embraced Alcoholics Anonymous. He confessed and apologized and overcame his vices.

Except for gambling.

Gambling, Weitzner wrote, was something he'd learned to control.

He hadn't.

By the end of March Madness, The Shrink's luck ran out. He lost big.

In the weeks following the college basketball tournament, Weitzner resumed familiar habits. He had confessed alcoholism and drug addiction on Eye on Gambling. He used the site to opine and answer personal questions and to share bits of his life.

"My life is an open book because of these forums," he wrote. "I do not mind sharing whatever anyone feels like asking me."

On April 2, his birthday, he wrote that he had dinner out with his wife.

On April 4, Easter, Weitzner watched his grandchildren jump on the pool cover. How, he typed, can children be so happy doing the simplest things?

On April 7, Weitzner joked about global warming. It was 90 degrees in Chesapeake, he wrote.

He posted again that evening, after he and Jackie visited a Norfolk law office where two attorneys witnessed newly printed wills with their signatures.

Weitzner kept the errand to himself.

As the sun began to set, he called Joe Vandercook.

The Eye on Gambling moderator considered Weitzner more of a father than a boss.

They talked daily. When they disagreed, they made up quickly.

Vandercook missed the call but phoned him back within minutes.

My wife and I are going to the Outer Banks, Weitzner said. My baby is in your hands, he said of the gambling portal. I know you'll take care of it. Do you want me to make a post to make it clear?

No, Vandercook said, laughing. I don't care who's in charge. It's not a big deal. You've gone on vacation before.

When are you coming back? Vandercook asked.

When are we coming back, baby? The Shrink asked his wife.

I'm not sure, they both said. Weitzner chuckled, and the conversation turned to something else.

Weitzner shared his vacation plans with the rest of Eye on Gambling in a 9:30 p.m. post.

"My wife and I will be going away for a trip... I won't be posting while we are gone... It seems like EOG keeps getting better each day with so many new posters... I feel like this place has always been a second home for me because of all of you... Thanks from the bottom of my heart... I am grateful to be a part of this Family and for all the support."

He spoke to his mother and so did Jackie. They apologized for not making it to Costa Rica for Somerstein's birthday.

You'll just bring me a bigger present when you come, she told Jackie.

Well, you never know, Jackie said.

That was odd, Somerstein thought, but she hated to pry.

They hung up, and Weitzner returned to his forum. He read the farewell notes and the well-wishes. He told them where he was going.

"It's some time I want to give to my wife... Duck, which is in the Outer Banks of North Carolina..."

Then Weitzner went silent.

The housekeeper found the bodies three days later, on April 10. The truth came in pieces after that.

The vacation was a ruse for a suicide pact.

Sometime after midnight, Weitzner and his wife went into a bathroom of their grand Hickory house, sealed the doors and lit two charcoal grills. The fumes would sap the oxygen from the air.

There was no choice, said the note they left behind.

They'd lost everything.

Kristin Davis, (757) 222-5208, kristin.davis@pilotonline.com